Welcome to Special Collections’ Spring 2019 exhibit: especially for bibliophiles!

“Master of a Hundred Arts”

Athanasius Kircher in 1655

Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680) was regarded as a great intellectual during his lifetime. With insatiable curiosity, access to the expansive knowledge networks of the Jesuit order, and the power to disperse his ideas in print, Kircher produced over forty “seat-cushion-sized” tomes on diverse subjects including hieroglyphics, musicology, geology, magnetism, comparative religion, and medicine.

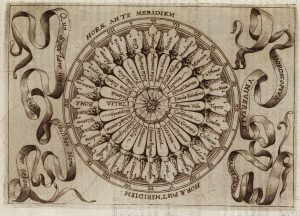

He curated and maintained a museum, the Kircherianum, in the Jesuit college in Rome, which contained artifacts and curiosities from his own travels as well as machines and instruments of his own design. The latter included contraptions such as the sunflower clock, which he believed demonstrated plants’ magnetic attraction to the sun and could also be used, under very carefully controlled conditions, to tell time. “A clock of this sort,” he noted, “can barely last one month, even though cared for with the greatest effort; thus, nothing is perfect in every aspect.”

Kircher also approached and presented his research with apparent glee. According to science writer Michon Scott,“Even if he lacked the rigorous approach of modern science, he delighted in his intellectual pursuits. Visitors to the Kircherianum sipped tasty liquids provided by mechanical barfing crustacians and heard his disembodied voice, fed to them through a hidden metal tube he spoke through from his bedroom. […] He once tricked the minister of his abbey into desperately searching for an organ that didn’t exist; what the minister really heard was Kircher’s Aeolian harp played by the wind. He launched dragon-shaped hot-air balloons with ‘Flee the Wrath of God’ painted on their underbellies. He dressed up cats in cherub wings, to the mild amusement of onlookers and the great annoyance of the cats.”

His copious works were widely read by his contemporaries throughout Europe and were even funded by popes and Holy Roman Emperors. Toward the end of his life, however, his reputation declined. His many bizarre hypotheses and bafflingly erroneous conclusions ultimately led to the dismissal of his work as ridiculous at worst and half-right at best. Kircher’s contemporary, Rene Descartes, scoffed that Kircher was “possessed of an aberrant imagination… more charlatan than savant.” Members of his own order pranked him in his later years by inventing a coded language for him to decipher.

Illustration from “Magnes sive arte magnetica”

Kircher is now considered to have made few to no original contributions to the bodies of knowledge which he studied. His books are valued more for their fantastic scope and fascinating illustrations than their scholarly content, although some of his ideas did seed modern fields of study and led to durable scientific discoveries. He is considered a founder of Egyptology, for example, although his attempts to translate hieroglyphs almost a century before the discovery of the Rosetta Stone were elaborately wrong.

Recent writing on Kircher positions him as an ingenious, prolific, and grandiose public scholar at the turn of the “scientific revolution.” He was a Catholic philosopher who sought fervently to make sense of nature’s mysteries and the wondrous workings of all things in an age when modern ways of thinking about the world were increasingly deviating from traditional concepts based on faith. “When Kircher was born,” wrote his biographer John Glassie, “almost everyone assumed that the Earth was at the center of the universe; at the time of his death almost every educated man willing to be honest with himself understood that it wasn’t. […] At the very least, as cultural critic Lawrence Weschler once put it, ‘Europe’s mind was blown.’” Another historian, Paula Findlen, summarized: “Kircher is a fascinating reflection of why and how science mattered in the mid-seventeenth century.”

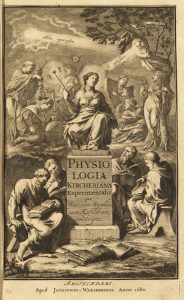

Frontispiece to “Physiologia Kircheriana experimentalis,” 1680

Works by (and about) Kircher at Portland State

Portland State University Library Special Collections holds two of Kircher’s works: Magnes sive arte magnetica (3rd ed., printed in 1654), and Physiologia Kircheriana experimentalis (1680). Magnes is Kircher’s second and largest work on electricity and magnetism, in which he describes the properties of various types of magnetism in the natural world, from the influences acting on heavenly bodies to the compelling attractions of music and love, and elucidates these with a series of practical experiments that include the sunflower clock. Physiologia is a compendium of Kircher’s researches in physics, light, acoustics, hydraulics, and a myriad of other topics, published by his student Johann Kestler in the year of Kircher’s death.

Curious readers can check out these books on Kircher from the PSU Library: The Last Man Who Knew Everything by Paula Findlen (CT1098 .K46 A738 2004); The Ecstatic Journey by Ingrid Rowland (Q127 .I8 R68 2000); A Renaissance Man and a Quest for Lost Knowledge by Joscelyn Goodwin (CT1098 .K46 G62 1979b).

Alongside Fr. Kircher’s books, we present two species of books as objects of information, design, and art:

Tiny Books! Smaller Selections from Special Collections

Tiny “Tales About the Sun“

The octavo binding (often abbreviated 8vo) gets its name and its small size from the number of pages formed when full sheets of paper are folded and cut to make a bound book.

Small books allowed scribes and printers to fit more text per volume and to make books portable, first as objects of personal devotion and later as “pocket books” to be inexpensively purchased, easily carried, and read at one’s leisure.

These tiny octavo and duodecimo books reflect publishing designs for small children, a Victorian fascination with miniatures, and the absorbing occupation of reading on the go from a handheld device.

The Art of Marbling

The origins of paper marbling are uncertain, but most scholars agree that a style like marbling, called suminagashi (“floating ink”) began in 10th-century Japan. This is where we find some of the oldest and exquisite examples of this art form. Japanese nobility used marbled papers as a background for their calligraphy.

Marbling is the earliest type of decoration used for the end-papers of books. Persians were the first to use marbled papers in books during the 16th century.

In her book, Decorated Book Papers: Being an Account of Their Designs and Fashions, Rosamond B. Loring explains the reason for using marbled end-papers. “In making a study of end-papers one finds that respect for the written or printed words early led men to protect their manuscripts from the wear a scroll or book was likely to get from handling… This gave the readers something to hold and prevented dirt and finger marks from soiling the manuscript.”

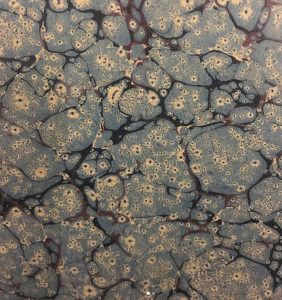

An example of a marbled endsheet

The technique of marbling paper is relatively simple. Oil colors are added to a bath of thickened water and the patterns that form on top are lifted by laying a sheet of paper upon it. The differing patterns are created by using styluses and combs of various kinds. Variations in the water, hand movements, and even dust particles make every piece unique.

Rosamond Loring’s book on decorated papers is also available at the PSU Library: Z271 .L85 2007.

Visit the Exhibit during Spring 2019

See the display of these extraordinary volumes in the first floor lobby (across from the elevators) in Branford Millar Library this spring term! Special Collections is open to the public by appointment on weekdays. Please contact us at specialcollections@pdx.edu with your inquiries or requests!

–PSU Library Special Collections Staff